In 2023, a lawyer in New York made headlines for submitting a legal brief full of case precedents that didn’t exist. He hadn’t invented them; he had asked ChatGPT to find them. GenAI generated the case names, dates, and even fabricated judicial opinions that looked highly realistic.

The lawyer wasn’t malicious. He was just credulous. He assumed that if a computer said it, it must be true.

In our sixth post on Re-thinking thinking: Authentic Intelligence, we face the most dangerous aspect of GenAI: Hallucination.

We are entering an era in which “sounding smart” and “being right” are no longer the same. If we don’t teach our students the difference, we aren’t just failing them academically; we are releasing them into a world where they can be easily manipulated by a confident algorithm.

It’s Not Lying, It’s “Bullshitting”

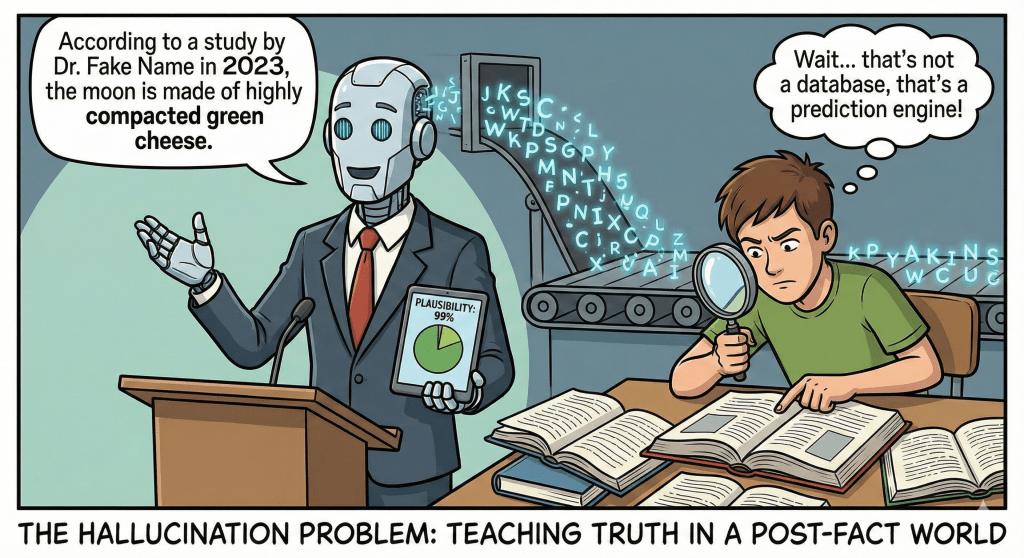

To understand why AI lies, students need to know how it works. A database (like Wikipedia) retrieves stored facts. But an LLM (Large Language Model) is not a database. It is a prediction engine.

When you ask it a question, it doesn’t “know” the answer. It calculates: “Based on all the text I have ever read, what is the most statistically probable next word?”

- The Truth: “The capital of France is Paris.” (High probability)

- The Hallucination: “The study on underwater basket weaving was conducted by [Fake Name] in [Fake Year].” (High probability that a citation looks like this, even if the facts are wrong).

There is a distinction between a Liar (who knows the truth and hides it) and a Bullshitter (who doesn’t care about the truth, only about persuading you). AI is the ultimate bullshitter. It prioritizes plausibility over accuracy.

The “Plausibility Trap”

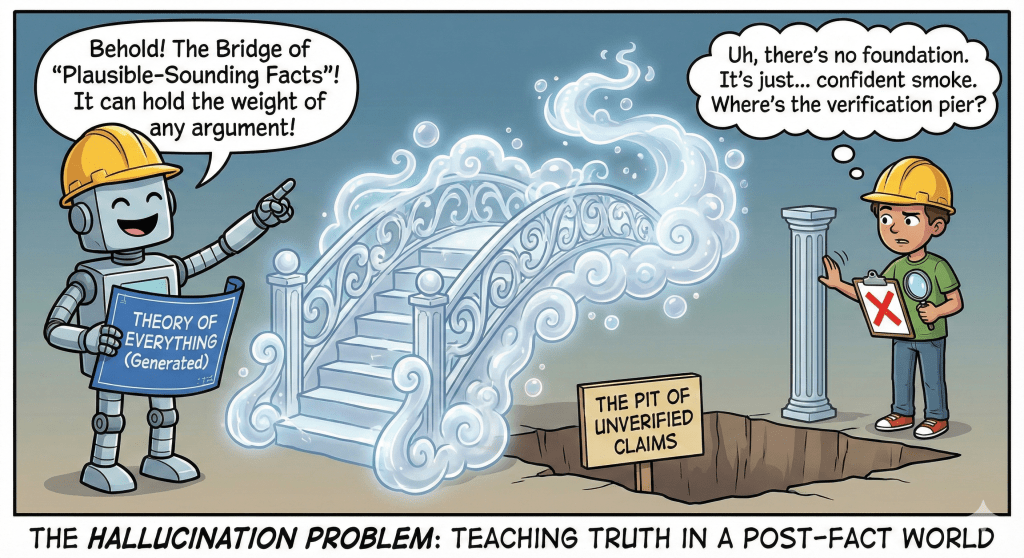

The danger for students isn’t that AI writes gibberish. The danger is that it writes compelling fiction.

When a student uses AI to research a topic they don’t understand, they fall into the Plausibility Trap. The AI explains a concept so clearly and confidently that the student accepts it as fact. This erodes the foundation of critical thinking: verification.

If we raise a generation that trusts machine output more than the verification process, we face an epistemic crisis. We are trading knowledge for “truthiness.”

The Solution: From “Consumers” to “Forensic Investigators”

We cannot fix the AI (hallucinations are a feature, not a bug). We must fix the student’s relationship with the AI.

We need to shift our teaching model from “Information Retrieval” to “Information Interrogation.”

1. The “Red Team” Assignment

Instead of asking students to generate an answer, ask them to break one.

- The Strategy: The professor generates an AI essay on the course topic (ensuring it contains subtle errors).

- The Task: The student’s job is to “Red Team” the document. Find the three errors. Verify the citations. Critique the logic.

- The Lesson: This teaches students that AI is a rough drafter, not an oracle. It builds the muscle of skepticism.

2. The “Zero-Trust” Research Policy

Universities should adopt a “Zero-Trust” policy for AI-generated data.

- The Strategy: If a student uses AI to find sources (which can be a helpful starting point), they must provide the primary source link (DOI or direct URL) for each claim.

- The Lesson: “If you can’t click it, it doesn’t exist.” This forces the student to leave the chatbot and enter the library (digital or physical) to verify the claim.

3. Teach “Probabilistic Thinking”

We need to add a new literacy to the curriculum: how LLMs actually work.

- The Strategy: A mandatory freshman workshop that visualizes how the token prediction works. Show them the “temperature” settings of an AI.

- The Lesson: When students realize the AI is essentially rolling dice to choose words, the “magic” fades, and healthy skepticism takes its place.

The Bottom Line

In the past, the scarcity in education was information. We needed libraries and lectures to give students facts. Today, information is infinite and cheap.

The new scarcity is judgment.

Our strategic goal is to produce graduates who are the “adults in the room”. The ones who, when the machine gives a confident, eloquent, and wrong answer, have the knowledge and the guts to say: “Actually, that’s not true.”